This is the bridge that gave Bristol or Brygstowe, the place of the bridge, as it was originally known. The bridge that made the city seems to have benn losing importance and interest in recent years. I suppose that compared to the other wonders to be seen around Bristol it does look insignificant but this is my history of it.

Why a Bridge There?

The original bridge was built at the place where one could be most easily built across the River Frome. A bridge across the Avon nearer its mouth would have been technologically very difficult, the land there was very prone to flooding and the town would have been very exposed to attack. The original Saxon (approx. 600 A.D. - 1066) bridge would have been built of wood.

About a quarter of a mile to the northwest of Bristol Bridge is the very narrow Johnny Ball Lane which runs from Lewins Mead to Upper Maudlin Street. According to "An A-Z History of 200 Bristol Street Names" by Grace Cooper, 1989, Johnny Ball Lane was named after John a Ball who owned the property adjoining the Franciscan Friary (Greyfriars) in Lewins Mead. It was originally called Bartholomew Lane because St. Bartholomew's hospital had a gateway at the foot of Christmas Steps. John a Ball is said to be partly responsible for the building of the first Bristol Bridge beyond Bristol Castle in Norman times.

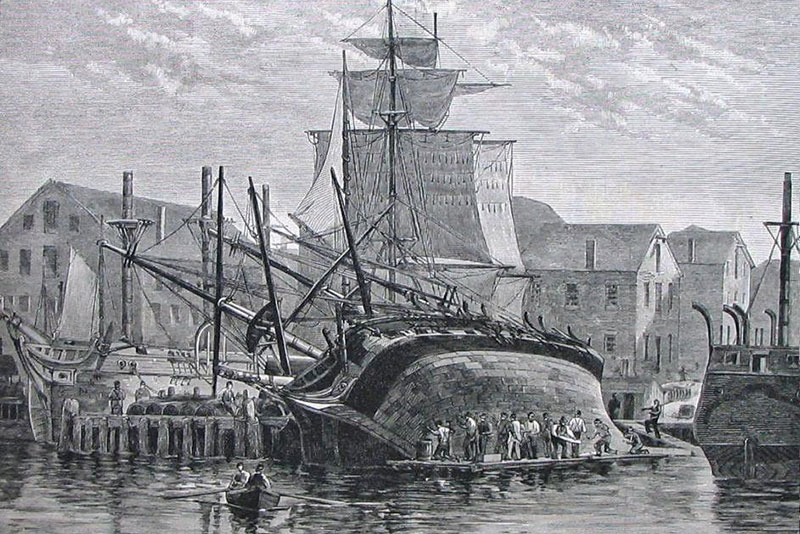

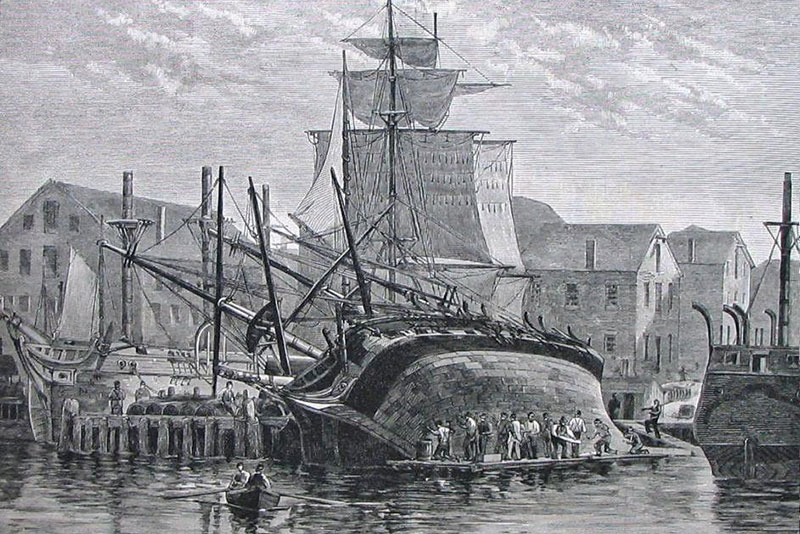

Shipshape and Bristol Fashion

Ships would make their way up the Avon until they reached Bristol Bridge and lay beached at low tide on the mud ready to be unloaded. The approach to the city from the sea was from the Kingroad at Avonmouth and up the tortuous River Avon. In 1662, the City Corporation decreed that because of the number of ships grounding in the Avon that no ship over 60 tons could attempt the passage under penalty of £10. Even up until the 18th century ships were often unloaded by waiting until they were beached at low tide and carrying the goods ashore. This put undue stress on the ships and many of the hulls were strained or damaged.

This helped give rise to the expression "shipshape and Bristol fashion". Shipshape was first used in the 17th century, and the Bristol fashion part was added in the early 19th century. Ships have been beached and laid on their side for repairs, called "careening" or "heaving down", for centuries. So, the expression "shipshape and Bristol fashion" could refer to a stoutly built ship capable of such treatment.

An Old Whaler Hove Down For Repairs, Near New Bedford, Massachusetts. A wood engraving drawn by Frederick Schiller Cozzens and published in Harper's Weekly, December 1882. Source: Wikimedia

The 1247 Bridge

A new bridge was built in 1247. This soon had houses down both sides, these were five stories high and overhung the river. In 1361, work on a chapel in the middle of the bridge was finished, which was dedicated to the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary on February 2, 1361. The chapel was 75 feet hign, and 21 feet wide, as the bridge was only 15 feet across, it overhang the sides of the bridge. It had gates at either end of a covered passageway, effectively creating a large gatehouse, controlling access into the city. The ground floor was used as a meeting room for Bristol’s council, with the chapel on the first floor, and a bell-tower above that.

It was in one of the houses on Bristol Bridge that Tobias Matthew was born on June 13, 1546. He was appointed Archbishop of York in 1606 but is important to Bristol for another reason. In 1613, Robert Redwood gave the Corporation his lodge in the Marsh (now King Street) for use as a public library, just the second in the UK. It was Tobias the donated the core collection of books for it. Tobias loved books; by the time he died on March 20, 1628 he had amassed a private collection of 3,000, quite a feat in the 17th century. The lodge was rebuilt around 1740 but by 1900 Bristol needed a new library and so Bristol Central Library was built.

Soon after the death of Henry VIII in 1547, churches were seized and The Chapel of St. Mary on Bristol Bridge, with the adjoining dwelling of the priest, was bestowed upon the city. The chapel extended right across the bridge, being erected over an archway similar to that of St. John's Church in Broad Street. The chapel was used as a warehouse until it was destroyed by fire in 1643.

The Council undertook the construction of two houses on Bristol Bridge of a character far surpassing the customary style of tradesmen's dwellings, which rarely exceeded two stories in height. The project seems to have been instigated by the receipt of a legacy of £100, bequeathed for public purposes by one Thomas Hart, and by the payment of one-half of a similar bequest of £40 left by Thomas Silk. Moved by a somewhat cool appeal for further assistance to carry out the design. Alderman Thomas White, of London, a member of a Bristol family remarkable for its liberal benefactions to the city, generously presented another £100. With these funds in hand, the Common Council, in 1548, gave orders for beginning the work, which was executed by workmen paid weekly by the Chamberlain

As the houses were to be chiefly of wood, a carpenter was brought down from London as superintendent, and was paid one shilling per day, the local workmen receiving eightpence, and the labourers fivepence per head. The first order for timber brought in seventeen large trees, and many more were required subsequently. The chimneys and fireplaces were of brick, which appears to have been imported, and was costly, two parcels costing £38. The bricklayer was paid one shilling per day. Some old glass was made available, and 258 feet of new glass cost the high price of sixpence per foot. Two of the Friaries were pillaged for some ornamental stonework. Probably owing to the workmen being left much to their own devices, the building operations extended over eighty-six weeks, and the total expenditure was no less than £495 13s. 9d., an extraordinary sum for that period. The houses were let for £6 13s. 4d. each in 1551

At around 10 o'clock on the the evening of February 17, 1646, a fire broke out at a Mr. Edwards, an apothacary, house. This soon spread and all of the houses, about 24 of them, from the center of the bridge northwards towards St. Nicholas Gate were destroyed. These were soon rebuilt using good quality materials that had been obtained fairly cheaply. In August 1646, Raglan Castle had been captured by Parliamentary forces. The buildings had soon been demolished and the materials, timber, stone, lead roofing and so on, had been sold by auction. Several enterprising Bristolians had purchased much of this material, floated it down the Wye and Severn rivers on rafts and used it to rebuild the houses.

Images of the 1247 Bristol Bridge

The 1768 Bridge

By 1755, it was obvious that Bristol Bridge was no longer fit for service, it had, after all, been built in 1247, and was now over 500 years old. Work on the bridge in 1747, brought to light a 40ft. long oak sill embedded in the masonry and this was thought to date back to the original bridge. In 1760, a bill to replace the bridge was carried through parliament by the Bristol MP Sir Jarrit Smyth. Many problems still had to be resolved; how much would a new bridge cost? Who was going to pay for it and how? Who would design it? Who would build it? What should it look like? Where should it be built? Would the original 1247 bridge foundations still stable enough? These and other questions caused heated debates which dragged on for years.

James Bridges had submitted plans for the new bridge in 1758 and after all the wrangling and arguments it was this plan that was finally adopted. In September 1761, a temporary footbridge was built but carriages and carts were soon using it. At this time it must be remembered that the City Council was not an elected body but a sort of "Gentleman's Club" made up of the rich and famous. Some prominent local families had been members of the council for generations. This also caused trouble in 1803 over the rebuilding of the city docks. Some members of the Council were also commissioners for the bridge. The main archways were completed at around 6 o'clock in the evening of June 25, 1768 when the last stone in them was positioned. The next morning Mr. George Symes Catcott was the first to walk over the bridge. He had paid 5 guineas for the privilege. The new bridge was finally opened to the general public in November 1768 and had cost £49,000. The builder was Thomas Paty, who between 1763 and 1768 was also one of the bridge commissioners. The commissioners were allowed to collect tolls for its building and upkeep. This wasn't the only source of income for the bridge as the city taxes on its citizens were raised as were the port taxes.

Images of the 1768 Bristol Bridge

The earliest images show domed booths at the ends of the bridge. These were the toll booths which were later turned into small shops and later still removed.

Several of the above images show a statue at the north end of the bridge at the junction of Baldwin and High Streets. This is of Samuel Morley (1809-1886). He was an industrialist, philanthropist, and abolitionist and was Bristol's Liberal MP from 1868 to 1885. The statue was created in marble by James Havard Thomas (1854-1921) and unveiled on October 22, 1887. Like many other city statues he has been moved around a bit. In 1921 to the Horsefair, later still to St James' Place near Broadmead and he now stands in Lewins Mead.

1793 Bristol Bridge Massacre

In 1793, after 25 years of toll collecting, the commissioner had over £3,000 in hand and people were clamouring for the tolls to cease and it was promised that the tolls would be scrapped on 29th September 1793, but a few days before this bills were printed saying that the tolls were available for sub-letting.

In 1786, the Act that controlled the taxes and tolls expired. This Act, like the Turnpike Acts, were only in force for 21 years at a time. The commissioners for the bridge reapplied for a new Act, this time with provision for demolishing houses on the approaches to the bridge. A corn and butter merchant, David Lewis, of Bridge Street, opposed the new Act and built up a sizable following. Following the introduction of the new Act it was David Lewis that purchased the first lease to collect the tolls on the bridge, and although he received recognition for forcing the leasing of the tolls from the commissioners it was his tollgates that were destroyed in 1793.

It was a hanging offence to destroy even the boards on which the tolls were publicised, but on 19th September 1793 a mob gathered and destroyed the tollgates. The Herefordshire militiamen were ordered to fire a warning shot over the heads of the rioters but a 60 year old plasterer, John Abbot, who was on his way home, was killed.

The inquest of this unfortunate man shows very clearly the feelings of both sides. The Mayor initially refused an inquest, then relented but directed the coroner to return a verdict of justifiable homicide. The jury had other ideas and pronounced a verdict of willful murder by the person or persons who ordered the militia to fire. The coroner eventually returned a verdict of murder by persons unknown.

By Saturday, 28th September the tollgates were back, as were the crowd, who destroyed the new ones. The constables and troops who were sent to disperse them were pelted with stones. The next day, Sunday, the barriers on the bridge were re-erected and the Commissioners tried to collect tolls on people using the bridge. The Riot Act was read three times and in the evening the crowd dispersed.

On Monday 30th September a mob arrived in force and had the Riot Act read to them three more times. The crowd ignored this and started pelting the soldiers. The Mayor had already ordered the soldiers to fire upon the crowd if resistance was met, this they did, without any warning. Ten more people were killed, and forty-five wounded. Many of those hit were reported as not being part of the mob but innocent bystanders, in fact one of those killed was a man visiting Bristol on business. The reward for the soldiers was that their commander, Lord Bateman, was given 100 guineas. With 11 people killed and 45 injured, it one of the worst massacres of the 18th century in England.

There were calls for charges of murder to be brought against the Council and members of the Commissioners as well as the publishing of the accounts for the new bridge. The Council for their part insinuated that a few radicals were behind the riots rather than believe that they and the Commissioners had mishandled the situation, both in terms of the finances of the bridge and what happened in those few days in September. All of those witnesses to the riots that could be found claimed that they were there as bystanders rather than face the consequences of admitting that they took part, which is hardly surprising given that they could, if the law was exercised to its fullest extent, be executed.

Between the Bridges: Some Trivia

John Latimer in his Annals of Bristol in the Nineteenth Century reported that the start of 1814 was very cold and that the harbour and the river under the bridge froze, "some thousands of persons are said to have enjoyed the novel experience of passing under Bristol bridge on foot."

The southern approach to the bridge, Victoria Street is relatively new. John Latimer says that "At a meeting of the Council on the 13th August, 1845, the Improvement Committee presented a report strongly condemning the narrow, inconvenient, and dangerous streets between Bristol Bridge and the railway station, and recommending the construction of a new thoroughfare, to be called Victoria Street. The expenditure required for this purpose was estimated at £84,510, but it was anticipated that £44,200 would be recovered by the resale of building sites, etc." It was at this meeting that the widening of Bristol Bridge at a cost of £8,000 was approved.

In March 1852, 7 years after it was first approved, work was due to start on the first £11,300 improvement of the area around Victoria Street. Under pressure from ratepayers, the work was postponed.

The 1873 Bridge Alterations

In the autumn of 1861, the scheme for widening Bristol Bridge approved in 1845 was again discussed by the Council. The idea was to remove the east side stone balustrade, add iron cantilevers and build the new walkway on that. Two of the stone toll-houses were to be removed during the alterations. This scheme would add about 14 feet to the width of the bridge.

When the work was done people were upset because instead of following the curve of of the bridge, the new roadway was level with the highest point on the bridge and there were steps at either end. The Council had to spend another £5,000 redoing the work and then people said the correction was done with little regard to the aesthetics of the bridge.

This was the age of the railroads and in 1864, the House of Commons was asked to approve a scheme to cover the river from the old Stone Bridge on the east end of the city center all the way to Bristol Bridge and build a railway on top of it. The line would go along Castle Street, Union Street, and the Pithay to Christmas Street where a station would be built. The proposal even got as far as getting royal assent but the cost, estimated at £700,000, was prohibitive and never carried out. Bristol would look very different today if it had.

It was not until March 1873, that work commenced on the west side of the bridge. The road was not widened further, but the stone balustrade was replaced with an iron one to match the new east side and the remaining two toll-houses demolished. All the work was completed in June 1874, and this is the bridge that can be seen today.

Images of the Bristol Bridge after the 1873 alterations

On March 11th, 1891, the Electrical Committee, in a report to the Council, recommended that 90 arc lamps of 1,000 candle-power each should be erected in the central streets. The yearly cost of lighting was estimated at £2,500, or double the expense of gas. The cost of the plant was estimated at £66,000, but it was anticipated that a profit would be made by furnishing 10,000 lights to places of business. On October 21st, 1892, another report of the committee recommended the building of an electric power station at Temple Back, at a cost of £13,346. This was an underestimate as a further £7,000 had to spent because of the marshy ground it was to be built on On November 20th, 1893, the works being in full operation, Bristol Bridge and the neighbouring thoroughfares were illuminated with great success. So, Bristol Bridge was one of the first structures to be lit using electricity in the city.

Bridge Parade

Originally called Bridge Place, Bridge Parade was a microcosm of Bristol's trade. It was a very short street that led to the south approach of Bristol Bridge from Victoria Street.

In 1776, 2 Bridge Parade was occupied Henry Burgum and his partner George Catcott who were pewterers. In 1791, Kingsmill Grove and Joseph Pounteney were recorded as being papermakers in Bridge Parade. On April 16, I795, the ship "The Brothers" from Waterford, Ireland captained by M. Leary docked in Bristol. Of its cargo, 280 casks of butter, 20 barrels of lard, 33 bales of bacon, and 22 barrels of pork was bound for Thomas Vining & Son of Bridge Parade.

On Thursday, August 5, 1819, William Elton died in his house in Bridge Parade. The directory of 1825 lists Samuel Tozer, druggist working in Bridge Parade. 1825 saw a rise in speculative investments, particularly Latin America, including an imaginary country, Poyais. The bubble burst and in December 1825, a couple of London banks went bankrupt along with many country banks. In June 1826, Bristol Parade bankers, Messrs. Pitt, Powell & Fripp closed.

In 1828, Bristol Savings Bank was situated at 1, Bridge Parade. Around this time David Cotterell & Co., woollen manufacturers had offices in Bridge Parade. On May 21, 1849, 5 Bridge Parade was leased from Charles Thomas to Alfred Ritson Thomas. The 1830 directories list #6 being occupied by attorney Henry Gillard as well as Greenslade, Bartlett & James, butter, corn and hop dealers. Henry Gillard was still there until at least 1861.

In the 1846 directories W. & F. Boucher, grocers, tea dealers, and provision merchants were at 5, Bridge Parade.

By 1851, the Bristol Savings Bank had gone as the directories list W. & F. Boucher, grocers, tea dealers, and provision merchants and Thomas Clifton & Co., wine and spirit merchant as occupying #1. The 1851 directory also lists #2 occupied by T. Sanders & Co. seed, corn, and hop merchants; #3 occupied by James Wintle, wholesale and retail linen and woollen draper, silk mercer, laceman, haberdasher, hosier, glover, & undertaker; #4 being occupied by F. & J. Amory, grocers and tea dealers and by William. M. Gibson, chemist and druggist; #6, by the Bristol and Clifton Trade Association and John Miller, attorney and S. W. Underwood, engraver and printer; and #7 by the Bristol and London Globe Tea Company.

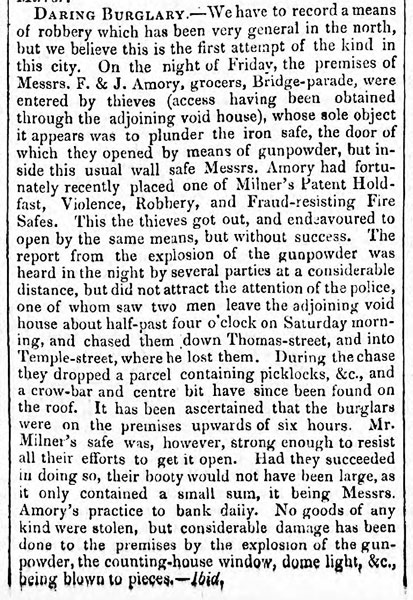

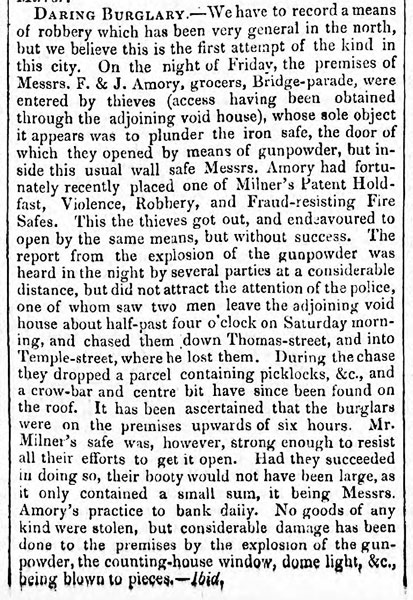

F. & J. Amory, grocers were still there in August 1954, as the place was burglarized (see below). Bristol United Gaslight Company had offices at #6 starting from September 1854. These offices moved to Canon's Marsh in 1857.

In 1861, W. H. Midwinter, artist & photographer was at 5, Bridge Parade. In 1863, H. Branscombe, leather worker was at 1, Bridge Parade; also at #1 were W. & F. Boucher, grocers, tea dealers, and provision merchants; Francis Parker, tea and coffer dealer at #2 along with Thomas Bowbeer and Wyld & Co., wine and spirit dealers; also at #2 were Ward & Son, hop merchants. James Wintle, wholesale and retail linen and woollen draper, silk mercer, laceman, haberdasher, hosier, glover, & undertaker was at #3; Edwin Fear, watch and clock maker was at #4 along with W. Bennett, boot and shoe maker; Daniel Stanton, collector of rates at #5; F. & J. Amory, tea dealers and grocers are listed at #5 and #6; Bristol and London Globe Tea Company were at #7. Elsewhere in the Parade but not listed where was Charles Bishop, umbrella and parasol manufacturer; someone named Lonsdale who was a dealer in stationery and fancy goods; and E. J. Orchard.

In 1864 and 1865, photographer T. S. Swatbridge had a studio somewhere in the Parade and in 1876 to 1878, photographer James Emmens also had a studio there at #5. From at least 1868 to 1870, #1 was being used by Samuel May Strange, Wedmore & Co. Between 1892 to 1897 #5 Bridge Parade was occupied by wine and spirit merchants, Crosswells Ltd. In 1871, Jas. G. Plumley, chemist and dentist and Edwin Fear, watch and clock maker were recorded as working from Bridge Parade. In 1873, Kinnersley Brothers, oil brokers, were at #2. In 1884, #2 was occupied by Ward & Co., maltsters; and #3 by Wyld & Co., wine and spirit merchants.

Martin Wintle took over the business of James Wintle who was mentioned in the 1851 and 1863 directories in 1902 and expanded into horse clothing.

The newspaper clipping comes from the August 18, 1854 issue of The Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian, Glamorgan Monmouth and Brecon Gazette. The article originally appeared in the Bristol Mirror.

The newspaper clipping comes from the August 18, 1854 issue of The Cardiff and Merthyr Guardian, Glamorgan Monmouth and Brecon Gazette. The article originally appeared in the Bristol Mirror.

DARING BURGLARY. - We have to record a means of robbery which has been very general in the north, but we believe this is the first attempt of the kind in this city. On the night of Friday, the premises of Messrs. F. & J. Amory, grocers, Bridge-parade, were entered by thieves (access having been obtained through the adjoining void house), whose sole object it appears was to plunder the iron safe, the door of which they opened by means of gunpowder, but inside this usual wall safe Messrs. Amory had fortunately recently placed one of Milner's Patent Holdfast, Violence, Robbery, and Fraud-resisting Fire Safes. This the thieves got out, and endeavoured to open by the same means, but without success. The report from the explosion of the gunpowder was heard in the night by several parties at a considerable distance, but did not attract the attention of the police, one of whom saw two men leave the adjoining void house about half-past four o’clock On Saturday morning, and chased them down Thomas-street, and into Temple-street, where he lost them. During the chase they dropped a parcel containing picklocks, &c., and a crow-bar and centre bit have since been found on the roof. It has been ascertained that the burglars were on the premises upwards of six hours. Mr. Milner's safe was, however, strong enough to resist all their efforts to get it open. Had they succeeded in doing so, their booty would not have been large, as it only contained a small sum, it being Messrs. Amory's practice to bank daily. No goods of any kind were stolen, but considerable damage has been done to the premises by the explosion of the gunpowder, the counting-house window, dome light, &c. being blown to pieces.

Artifacts from some of the businesses of Bridge Parade

Market tokens such as the one for W. & F. Boucher above were receipts for deposits paid for returnable packaging such as crates or sacks. When the packages were returned along with the token, the money was refunded.

The Pyramid

The former Norwich Union Building which stands at the north end of the bridge, on the corner High and Bridge Streets is one of the ugliest buildings in Bristol. It didn't look that great when it was built in the 1962 but in 2022 it been empty for nearly 20 years. But, next to it is an odd roughly pyramid shaped structure.

The odd roughly pyramid shaped structure next to the old Norwich Union Building

The pyramid is simply an entrance with a set of steps leading down to a couple of 13th century cellars under High Street.

13th century cellars under High Street

This whole area was heavily bombed during WWII and many of these cellars or at least the original entrances to them were lost. There are plans, in 2022, to redevelop this corner of Castle Park.

Sources and Resources

An A~Z History of 200 Bristol Street Names - by Grace Cooper, 1989, Bristol and Avon Family History Society

Annals of Bristol in the Nineteenth Century - John Latimer, 1887

Annals of Bristol in the Seventeenth Century - John Latimer, 1900

Bristol Live - Castle Park changes revealed: First images of major plan for eyesore site at St Mary le Port

Bristol Live - Delving into the medieval vaults you never knew existed in Bristol

Bristol Live - Major plans to transform eyesore St Mary le Port site in Castle Park approved

Bristol Museums - Hugh O'Neill, Bristol Bridge, 1823

A Descent Among Writers on Bristol History and Biography - by George Pryce (1858)

Geograph - Images of Johnny Ball Lane by Derek Harper

A half-hidden route to the past: Bristol’s Johnny Ball Lane

An introduction to Market Tokens

Looking at Buildings - The Central Library

Market Tokens

Norwich Union Building, Bristol, UK

Sixteenth Century Bristol - John Latimer, 1903

Wikimedia - An Old Whaler Hove Down For Repairs, Near New Bedford

Wikipedia - Tobias Matthew

This page created March 12, 2022; last modified August 7, 2022

The newspaper clipping comes from the August 18, 1854 issue of

The newspaper clipping comes from the August 18, 1854 issue of