Religious Dissent

The Puritans were moving farther and farther away from the established church, the various sects were becoming as intolerant of each other as they were of the church they had split from.

In 1640, five Puritans determined they would no longer submit to the form of worship set out in the book of Common Prayer and the Elizabethan Settlement, and they began to worship in Mrs Hazard's house in Broad Street. The others were Goodman Atkins of Stapleton, Goodman Cole, a butcher of Lawford's Gate, Richard Moore, a furrier of Wine Street, and Mr Bacon a young Minister. This congregation soon grew to 160 people and they had their own Minister, Mr Pennill. Others followed their lead and in 1641, Dennis Hollister, whose granddaughter would marry William Penn in 1696, and another man were brought before the magistrates for keeping a 'conventicle', a place of worship other than an established church. This type of persecution only stiffened people's resolve and even added to their numbers.

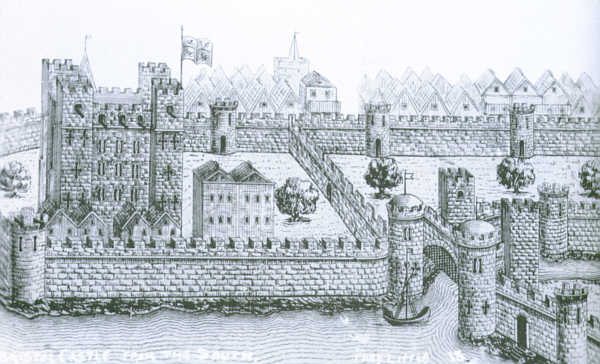

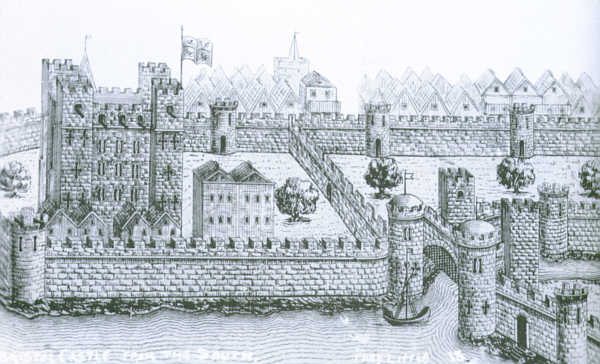

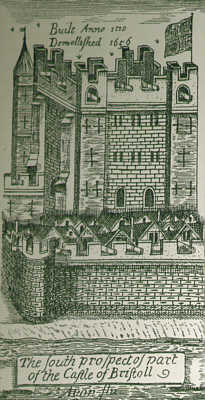

By now, it was obvious to practically everyone that Civil War was a distinct possibility, if not inevitable. The castle was put into a state of defence. The buildings that had sprung up around the castle were demolished. A hundred musketeers were placed on guard each evening and all the city gates were provided with warning drums.

Bristol Castle

Illustration by Fred Little

From "For King & Parliament" by John Lynch (Sutton, 1999, page 36)

Civil War

October 1642 saw the first hostilities of the Civil War, with the Battle of Edgehill. Bristol still hoped for a settlement but in early December opened it's gates to Colonel Essex and the Parliamentarian forces. He realised that the city was vulnerable to canon fire from the north and ordered the erection of earthworks around the city. The old wall from Redliffe Hill to Temple Meads was strengthened. A wall and trench from Temple Meads to Lawfords Gate, in Old Market, was built. This was then extended to Stokes Croft, Kingsdown, St Michaels Hill, Brandon Hill and back down to the Water Fort on the Avon. The wall and ditch was now three miles in length. Bastioned forts were now built at Prior's Hill, Windmill Hill and Brandon Hill Hill. The Windmill Hill fort was enlarged and renamed Royal Fort. The name still remains in the name of the

University buildings that now cover the site. In November 1642, the castle floors were replaced or strengthened to take the weight of canon.

Bristol's defences during the Civil War (1642 - 45)

The section of trench dug between Brandon Hill and Prior's Hill proved to be very hard work as it had to be dug out of rock. This section was never to be properly finished, with disastrous results in 1643.

These defences must have been expensive in both terms of money and manpower. Parliament did help with grants but most of the cost was borne by the people of Bristol themselves.

Essex proved to be a bad governor, spending most of his time feasting, drinking and gambling. When a soldier complained to him that they hadn't been paid, Essex shot him dead. Essex was arrested for this and the far better tactician, Colonel Nathaniel Fiennes replaced him.

Although occupied by Parliamentarian forces there were still plenty of Royalist sympathisers in the city. A merchant, Robert Yeamans, bribed a Captain and three lieutenants of the city guard and gathered a band of around thirty co-conspirators, who were sworn to secrecy by George Boucher, a friend of Yeamans. King Charles, at Oxford, was informed that a plan to hand the city over to him was afoot and Prince Rupert was dispatched with an army to take advantage of this. On March 7th, the armed conspirators assembled at Yeamans house, which was opposite the Guard House in Wine Street. One of the bribed officers was to surrender his men at midnight, at the same time one of the others was to take his men to Bouchers house near Frome Gate. When the Gate was seized it was to be opened, another band of men, gathered at Thomas Milward's house on St Michaels Hill, would enter the city. Other bands of men would attack the other gates. When the gates were captured, the bells of St Michael's and St

John's would be rung, Prince Rupert, waiting at Cotham, would enter the city through Frome Gate and occupy it.

The plan was a success, right up to the moment they assembled at various points around the city, when Fiennes had them all arrested. The chances are that the bribed officers had informed him of the plot as soon as they found out the details. Around 60 people were arrested, mostly poor men, and of those only four were put on trial, even two of these were reprieved. Yeamans and Boucher were hanged, instead of being released the others had to ransom themselves. Fiennes himself did not expect to make much out of the poor men, in a letter to his father he wrote he didn't expect to get more than £3,000 from all of them. Yeamans and Boucher were hanged in front of Yeamans house in Wine Street and between them they left 16 children.

King Charles wanted a triple attack on London during 1643. The problem was that the army to the north would leave Hull in Parliaments hands. The Cornish army would leave Plymouth in a similar position and the army in Wales when advancing to London would likewise leave Bristol and Gloucester under Parliamentarian control. To ensure the successful seizure of London these important cities must be taken.

After severely defeating the Parliamentarian army at Roundway, Wiltshire on 13th July 1643, Prince Rupert left Oxford on the 18th July to join forces with the Western Army and attack Bristol. On Monday 23rd July 1643 the campaign against Bristol started. Prince Rupert with 20,000 soldiers, Colonel Fiennes had 2,300 soldiers and 15,000 - 20,000 men, women and children to defend. The towns defences seem strong and Rupert lacked canon, but he obtained some by the capture (or surrender) of eight ships off of Avonmouth. The canon were bought ashore and bought to Bristol.

The attacks on Monday and Tuesday were easily repulsed and so an attack at six points was planned for Wednesday. At Temple Gate, Redcliffe Gate, Stokes Croft and St Michael's Hill the attacks were unsuccessful. Better was done at Prior's Hill Fort but Blake, who went on to fame as an Admiral, managed to beat back the attackers. The sixth point of attack was at the rampart between Brandon Hill and Royal forts. This is the place where the ditch was not properly constructed due to the rocky undersoil. Captain Washington whose descendant, George, went on to great things in America, was detailed to lead between 200 and 300 soldiers against this area. Armed with fire-pikes his men scattered the defending cavalry and soon leveled off the ditch. Calling for reinforcements, his men occupied the Cathedral and had forced their way to Frome Gate.

Fiennes was now in dire straits, his outer defences had been breached and he still had men in the outlying forts. He sent messengers to the forts, recalling the men to within the city walls. Blake at Prior's Hill didn't receive the message but managed to hold on to the fort for another 24 hours before being forced to abandon it.

The situation had become hopeless and Fiennes entered into negotiations. It was agreed with Prince Rupert that the Parliamentarians should be able to leave the city under arms. Rupert agreed that there should be no pillaging of the city when his army entered it.

As soon as the Royalist army entered the city there was, as might be expected, much pillaging and looting. Some inhabitants lost everything, houses were broken into and ransacked, shops were looted and to add insult to injury the soldiers were billeted into the very houses they had just wrecked and the occupants turned out into the streets.

Prince Rupert and Sir Ralph Hopton, who had led the Southern Army argued about who should become Governor of the newly won city. King Charles arrived and settled the matter by making Rupert Governor and Hopton Lieutenant-Governor.

Fiennes was later put on trial for abandoning the city and several people stated that he had played no creditable role in the whole affair and could have still won the day. Military officers, including Fairfax and Cromwell himself, said that Fiennes had done all he could. His defences were broken and he was heavily out-numbered.

The city was now fined for it's support of Parliament, and a gift of £20,000 demanded from its inhabitants, this was in addition to the £300 demanded as payment to the troops that had occupied it and various other taxes imposed. In 1644 the plague returned and carried off 3,000 people. The coming of Winter eased the problems, 81 people died in one week in September, but a month later the number was reduced to 32.

In June 1645, Cromwell and his New Model Army heavily defeated the Royalists at Naseby, and it was clear that if Bristol could be regained then the support of the Royalists in the west of England would dwindle.

At the end of August, Parliamentary warships blockaded the Avon and Fairfax surrounded the city. The King moved westwards hoping to relieve Bristol, mindfull of the advancing army, Fairfax now demanded the surrender of the city. Rupert tried to string out the negotiations, but Fairfax realising he was playing for time, attacked at 2am on 10th September. Although Cromwell had stationed himself on Ashley Hill he appears to have played no part in the battle.

Lawford's Gate and Old Market was soon captured opening the way to the Great Gate of the castle. Prior's Hill fort was taken just before sunrise and it's defenders massacred. As Fiennes did before him once the outer defences were broken, Rupert now started negotiations for surrender. By now there were several fires in the city and the surrender was accepted on condition that the fires were extinguished. As Cromwell wrote in a letter "fearing to see so famous a city burnt to ashes before our faces". Rupert and his followers were allowed to leave under arms. Charles I, who was Prince Rupert's uncle, never forgave him for capitulating so easily and from then on the word "Bristol" could not be mentioned between the two men.

When the Parliamentarians entered the city they found "it looked more like a prison than a city, and the people more like prisoners than citizens; being brought so low with taxations, so poor in habits, and so dejected in countenance; the streets so noisome, and the houses so nasty as they were unfit to receive friends till they were cleansed".

The writer of the above obviously hadn't been to East Street, Bedminster any Saturday night, - it always looks like this!

On 17th September the House of Commons agreed that the following Sunday should be set aside as a day of thanksgiving and that collections should be made on Sunday, 5th October for the maimed soldiers and "for the relief of many distressed and plundered people of Bristol and places adjacent".

On 14th March 1646 the King's army surrendered to Fairfax in Cornwall and on 5th May he surrendered himself at Southwell. King Charles I was defeated, but the Civil War was far from over. Charles was executed in 1649.

The End of the Castle

On 15th November 1654, Parliament decided that "Resolved, that Colonel Birch do make a report to the House of the proceedings of the Committee for retrenching the forces. Colonel Birch, accordingly, reports the proceedings of the said Committee, and their resolutions, after advice with eight officers, appointed by his Highness, touching the garrisons in England, which they conceived fit to be demolished, and which to be kept up; which the Committee thought fit to be presented to his Highness, the Lord Protector, and to desire his Highness to consider and direct what further abatement may be made of the forces in England, and of the garrisons and forces in Scotland and Ireland; and that they appointed a Sub-committee to attend his Highness therein: which was done, accordingly, but have not yet received an answer, therein, from his Highness."

Colonel Birch reported back that "The garrisons which they thought fit to be dismantled, demolished, and made untenable were these; Bristol Castle and Fort, Denbigh, Taunton, Mersey-fort, Carnarvon, and Shrewsbury. The garrisons to be continued were: Tenby, Carmarthen, Liverpool, Chepstow, Beaumaris, Yarmouth, Jersey, Guernsey, Scilly, Isle of Man, Isle of Wight, Mount in Cornwall, Pendennis, St. Mawes, Cackut, Hurst, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Dover, Sandwich, Warmouth, Deal, Sandown, Tilbury, Languard Fort, Hull, Scarborough, Berwick, Carlisle, Tower of London, Windsor Castle, Portland, Kelso, Southsea, Tinmouth and Hascott in Suffolk."

On 23rd November 1654, a report made before parliament said that "For Bristol Castle, it was a place of no great strength, yet it was convenient for a citadel, and might be made use of to that purpose. For Bristol Fort, it was very regular, and might be kept with a small number. That it was the practice of all nations, and he mentioned that of France, that in all populous cities, there used to be citadels, and therefore, he thought this also might deserve farther consideration." (Guibon Goddard's Journal)

It obviously wasn't and when Parliament decided to destroy many of the castles, Bristol's were amongst them and the following order was received from London...

OLIVER P.

These are to authorise you forthwith to demolish the castle within the city of Bristol, and for so doing this shall be your warrant.

Given at Whithall,

28th day of December, 1654.

To the Mayor and Commonalty

of the City of Bristol.

Nicolls and Taylor in "Bristol Past and Present" (Vol. III, Arrowsmith, London, 1882, page 36) says that...

On the 28th December, 1654, Cromwell's order was sent for immediate demolition of the castle; but although our Calendars say that this was accomplished in a fortnight by the householders, who each had to work in person or else pay a substitute, it was clear that the work was not so speedily executed, for on February 28th, 1655, Major ------- [sic] brought another peremptory order from the lord protector, and the major declared he would stay until the work was completed, notwithstanding the badness of the horse quarters and the dearness of the place to the soldiers. The fortnight of hard work must therefore be transposed from Christmas to March, 1655.

Work began on the demolition on 4th January 1655 but it was still in progress in October. The magistrates ordered that each citizen should pay a labourer a day's wages each week until the Castle was gone. It is said that after this order was given the castle was totally demolished in a fortnight. Whatever the truth of this, there is now no trace of the castle left apart from the foundations.

In 1655 a bridge was made over the ditch of the castle's west end and Castle Street was made through the site of the castle "to the great convenience of the citizens".

Even this wasn't quite the end of the castle. In July, 1672, according to John Latimer's "Calendar of the Charters &c. of the City and County of Bristol" (Corporation of Bristol, 1909, page 157) "the Common Council, on payment of £2,989, obtained a conveyance of the fee farms and Castle."

In 1685 Thomas Goldney, sometimes spelled Gouldney, amongst others, was fined £200 for refusal to take an oath. This fine was eventually paid by his son, also named Thomas. By 1688 the Corporation was encouraging the building on the Bristol's castle grounds. Thomas Goldney the elder, bought sites for four houses on Castle Green for £200. As part of the payment the Corporation took into account £50 of the fine. (The Goldney Family)

Remains

Despite Cromwell's efforts, only the Norman Great Keep was totally demolished and isolated parts of the castle survived until the 1930's and 40's. Unfortunately, what the Luftwaffe didn't destroy, the developers did. Throughout its history people built dwellings and other buildings very close to the castle walls and in some cases the walls were incorporated into these buildings. This ensured that at least part of the castle was preserved.

Using William Wyrcestre's 1480 notes, John Evans in his 1824 book, "A Chronological Outline of the History of Bristol", wrote of the castle, with relevance to the buildings of his day...

The great tower, called the dongeon, donjon, or keep, was situated just within this gate, between Castle-street and Castle-green, taking the Bear-and-Ragged-Staff public house as built upon the site of its north tower, and the house occupied by Mr. Hunt, cutler, as projecting westward of its south tower. The base of the whole tower extended about two-thirds of the distance from the point noted towards Roach's Lane, now called after the Cock-and-Bottle public-house at its north-west corner.

South of the dongeon, standing between the yard of the George Inn, now a wool-warehouse, and Golden Boy Lane, but nearer to the former, stood the Governor's House or Constable's Hall; westward of which, at the termination the George-Yard, and close to the water's edge, stood a round tower, forming the extreme point of the Castle-walls on that side.

St. Martin's Church stood north of the dongeon, at the entrance of Castle-Green, and adjoining time Tower connected with New-Gate.

There was a double wall on the north side of the Castle; the inner wall stood on the summit of the bank marked the frontage of the houses on that side of Castle-green. Parts of the outer wall still remain.

Where the large house in a garden or court adjoining Messrs. Ambrose Oxley & Co.'s warehouse is situated a square tower on the inner wall, and a larger tower on the outer wall or terrace. From these two towers the wall that separated the outer ward, ballium, or court, from the inner yard, cutting diagonally the lower part of Cock-and-Bottle lane towards Castle-street, crossed the latter to a small tower on the bank of the Avon, which tower stood mid-way between the extreme western round tower above noticed, and a square tower next to the Water-gate, where the ditch is entered from the river, the place of the unfortunate second Edward's debarkation, in his attempt to seek an asylum at time Island of Lundy.

The sally-port was in Queen-street, at the Brewery-warehouse, in an inner wall on the bank of the ditch; that inner wall being continued from the Water-gate to the eastern or Nether-gate, at the end of Castle-street. From the Water-gate the outer wall followed the curve the Avon, close to the water's edge, to a round tower, between which and the western round tower, near the Mint, the Water-gate formed a point nearly central. The outer wall, proceeding hence north-eastward, towards St. Philip's Church, continued up the present Tower-street to the eastern gate, at the end of Castle-street.

The space enclosed by the inner and outer wall on this side, into the middle of which Queen-street descends was called the King's Orchard, or Castle-Mead, and comprised two acres.

The site of the houses without the Castle walls, between Tower-street and Church-lane, south of time Old Market, was William of Worcester's garden. The Cross erected by Philip le Mare, in 1279, stood near the house, just without the nether gate.

From this gate the wall continued, on the bank of the ditch, to a square tower behind the back of Mr. Hartland's house and the Cold Bath; and the ditch washed the foot of a square tower which commanded Aelle or Weir bridge, whence the outer wall continued onward to Newgate.

Within the Castle-wall, on the eastward, the ground, now occupied by houses in the angle formed by the north side of Castle-street and the east angle of Castle-green (which division of it was formerly called Tower-street), comprised, next to Castle-street, the servants' apartments. In Castle-green are still to be seen the walls and arched ceiling of the entrance porches to the Great Hall and the Chapel; adjoining whereto, northward, and facing the longer division of Castle-green, westward, were the Royal apartments. At the back of Mr. Hartland's house, situated behind the Gas company's late offices, still stands a castellated look-out, indicating the back of

those apartments.

That part of the inner ballium or ward which lay next to the Avon was called the Great Garden.

Many of the streets in the above account are now gone, or have had their course altered. Most of the area can still be seen in the following 1901 and 1902 Ordnance Survey maps of the area.

Bristol NE 1902 Ordnance Survey

Bristol NW 1901 Ordnance Survey

In their book, "Bristol Past and Present" (Arrowsmith, 1881, pages 74-79), J. F. Nicholls and John Taylor give another description of the castle. This is again based on William Wyrcestre's 1480 notes and the remains of the castle that were still present at the time. It is reproduced, along with their illustrations, below...

Commencing at the river Avon, it crossed the west end of Castle street; its barbican stood on the site of the house at the junction of Peter and Castle streets, extending towards St. Peter's church; between this barbican and the wall there was a deep dry artificial fosse crossed by a drawbridge. The bottom of this fosse was about the width of the second house in Castle street, it then ran down on the western front of the Bear and Ragged Staff and Catherine Wheel public houses; at the corner of Castle green, where the school house now stands, it bent round to the N.E., both fosse and wall being continued through the Newgate on the hill, at the bottom of which there was a drawbridge. This bridge was over a leat of the river Frome, which had been brought to the foot of the hill to form a ditch. About ten feet from the water's edge rose the lowest of the north walls to a height of from twenty to thirty feet, and from the inner edge of the platform within this wall rose another embattled wall of about the same height, so that here the castle presented a double terraced front, we believe of from fifty to sixty feet in height, reaching to and guarding the hill top. At the east angle of this wall where the hill had lowered considerably, the leat had been widened to form a mill pond, in which stood the cucking-stool for fraudulent brewers and scolding wives; the castle mill was on the north-eastern or outer edge of the ditch and pond. From thence another deep artificial cutting led a portion of the waters under what is now the street known as Lower Castle street as far as the end of Old Market street. Here there was a small foot drawbridge, opening into a green (now Old Market street). From this bridge the moat and wall bent obliquely round to the west; the covered moat still exists, and runs under the first four houses at the south-east end of Castle street, after which it emerges, and is continued as an open watercourse, passing under a bridge Queen street until it joins the Avon in the angle where the river makes a great bend to the south. At this junction stood the water gate, guarded by five towers. The space thus enclosed by crenellated walls contains about three and three-quarter acres. There was, however, outside this on the south-west the king's orchard, which contained two acres more; this was surrounded by a "bastyle," i.e., an embattled-wall without towers. This wall enclosed the land whereon St. Philip's National School now stands.

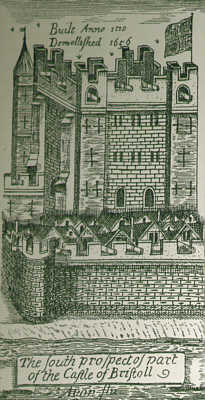

Great Dungeon Tower of Bristol Castle

Image from "Bristol Past and Present" by J. F. Nicholls and John Taylor (Arrowsmith, 1881, page 75)

Continuing J. F. Nicholls and John Taylor's description of the castle from their book, "Bristol Past and Present" (Arrowsmith, 1881)

Strong and spacious as the great castle was for 600 years but few relics of its buildings remain, and its written records are almost as scanty. The surviving appellations of Castle green, Castle ditch, Castle precincts and Castle street designate certain portions of its locality and a few underground cellars, arched doorways and dark dungeons will help us, with the aid of William Wyrcestre, to trace its principal buildings.

The ichnography was as follows: The ground was divided into three portions, 1st, the outer 2nd, the inner ward; and 3rd, the king?s orchard. The two first plots of ground, between the two rivers covered the whole breadth of the hill which gradually widened and decreased in height from Peter street to the Old Market. The outer ward was separated from the inner by a crenellated wall which, commencing at the outer north wall, crossed the hill by the line of Cock and Bottle lane to the water tower upon the Avon. Nearly in the centre of this ward Robert the Consul built his famous Donjon tower, apparently upon the plan of the Great White tower of London; the present Castle street runs nearly through the centre of the site of this famous tower. Its walls were, in the foundation 25 feet in thickness, and at the top, under the lead covered roof 9 feet 6 inches. In shape it was a parallelogram, the greater length on the inside being from west to east 60 feet, the breadth from north to south 45 feet. Its outer dimensions were 110 feet x 95 feet. It was strengthened by four square towers, one at each corner. The south-west or "mightiest tower" was 30 feet higher than the others, and the thickness of its walls was there 6 feet. This edifice was all built (faced) of Caen stone brought specially from Normandy.

The keep, with the exception of that of London, was the largest in the kingdom. Its size and importance will be seen by comparing its dimensions with those built within 50 years of its date.

Tower of London -116 x 96ft

Bristol - 110 x 95

Norwich - 110 x 92

Rochester - 75 x 72

Hedingham - 62 x 55

Guildford - 47 x 42

This page created April 8, 2005; last modified November 6, 2022