World War I

Before starting on the blitz of World War II, it should be remembered that although Bristol didn't suffer any material damage in WWI a lot of Bristolians gave their lives in the fighting. Roughly 55,000 men from around Bristol enlisted of which about 7,000 died. More than 3,000 of those that enlisted were Clifton College Old Boys. These, between them, won 5 VCs (Victoria Crosses), 180 DSOs (Distinguished Service Orders) and 300 MCs (Military Crosses). Of these Old Boys 580 died. 137 men who had been to Bristol University also died, these gained 1 VC, 2 DSOs, 42 MCs and a DFC (Distinguished Flying Cross).

The most famous of the Clifton College Old Boys was Douglas Haig (1861 - 1928). He became the Commander-in-Chief of the British army in France and planned the Somme offensive of 1916. He was created an Earl in 1919 and retired as a Field Marshall.

347,045 horses and mules passed through the re-mount depot at Shirehampton, of which 317,165 came from overseas. Planes were being produced at Filton, whilst over factories in and around Bristol were providing the military with motor cycles, explosives, boots, uniforms, chocolate, tobacco and mustard gas.

The Clifton Chronicle of January 1916 reported the wedding of Miss Mary Hunford Jones and Captain F. Birkett of the Queen's Royal West Surrey Regiment at Christchurch, Clifton.

"The Bride's dress was of khaki honeycomb cloth trimmed with skink, nigger brown velvet hat trimmed with silk and veil to match and she carried a shower bouquet white carnations and lilies tied with the colours of The Queen's Regiment. The bridesmaids wore French gray cashmere.

The groom, who was educated at Monkton Combe School, joined his battalion in France in December 1914 and was slightly wounded in the arm. He rejoined and was dangerously wounded in both legs in May 1916, brought home and made a slow recovery."

A little known fact was that Avonmouth became the centre of the British chemical warfare manufacturing during 1917. The plant there made 20 tons of dichlorethyl sulphide - mustard gas - a day. In December 1918, the plant Medical Officer reported that in the six months it was operational, there were 1,400 illnesses reported by its 1,100 workers - all attributable to their work. There were 160 accidents and over 1,000 burns. Three people died because of the accidents and another four died as a result of their illnesses. These included blisters, gastritis, bronchopneumonia, mental problems and problems with eyesight. There were thirty resident patients in the factory hospital tended by a doctor and eight nurses. The gas produced by the plant didn't arrive in France until September 1918, two months before the Armistice.

World War II

At 11am 3rd September 1939 war was declared against Germany. It was obvious that bombers would be able to reach every part of the United Kingdom and air raid shelters were built. On 19th June 1940, a lone bomber attacked the Bristol Aircraft works at Filton. Whittocks End was bombed on 3rd July, but the only casualties were a pig, five ducks, two rabbits and a hay rick. This was just a warning of what was to come. Bristol would become the 5th most bombed city in the UK.

On 22nd - 23rd August more than 400 bombs fell in and around Filton, the main target was the aircraft factory which was very badly damaged. On the morning of 25th September 1940, 300 bombs were dropped, 160 of them hit the aircraft factory, 6 of these unfortunately hit the air raid shelters there. Hundreds were killed or injured. Eight enemy aircraft were shot down. On 27th September ninety planes attacked the city but were driven off by the RAF, seven enemy planes were shot down on this

occasion.

On 2nd November more than 5,000 incendaries and 10,000 high explosive bombs fell on the city. More than 200 people died and 700 were injured. 10,000 houses were damaged or destroyed, as were many historic buildings. Hitler claimed that Bristol had been totally destroyed, later on in the month it very nearly was.

The worst raid was on the night of Sunday, 24th November 1940. The raid started with pathfinder flares illuminating the city at 6.50pm. In a single night the city had changed forever. The Lord Mayor, Alderman Thomas Underwood, was to write in 1942, that that night "The City of Churches had in one night become the city of

ruins". Much of the area around Wine and Castle Streets, in fact the whole of the area which is now Castle Green, was reduced to a mass of rubble. The damage wasn't confined to this area though, bombs fell on College Green, Park Street, Queen's Road, Redcliffe Street, Thomas Street and Victoria Street.

Many historic buildings were lost forever. St. Peter's Hospital, the Dutch House, the city museum, the art gallery, much of the university, Prince's Theatre, Upper Arcade, three Norman churches, seven newer churches, eight schools, and many alms-houses, cinemas and factories all disappeared, along with 10,000 houses.

On 3rd January 1941, 10,000 incendaries fell on the city, the next night another 7,000 fell on the docks at Avonmouth. On 16th January, an eleven hour raid caused more destruction to Bristol and Avonmouth.

On 11th and 12th April, in the Good Friday Raids, 150 bombers once more attacked the city. The centre of Bristol suffered even more damage, as did Knowle, Hotwells and Filton. In this raid 180 people died and 381 were injured. 6,500 anti aircraft shells were fired in the defence of the city. 25th April 1941 saw the last major raid on

Bristol. Brislington, Knowle and Bedminster were all hit. Sixteen people were killed and 28 injured. Another 1,200 houses were damaged.

Altogether there were 78 air raids on the city. A total of 1,299 people were killed and 3,305 injured.

When I was growing up in Knowle in the 1960's we used to play in the old bomb craters, not realising what they were - or what they meant.

Memories

My dad was born on October 21, 1930 and was still a boy during WWII. I remember me telling me that apart from the raids, living in war-time Bristol wasn't as terrifying as you might think. Like lots of other kids, after the raids, he'd go out looking for shrapnel, spent shells and even bits of plane. He'd take them to school and he and his friends would compare what they'd found.

He told me about a raid when there was a lot of damage done to Park Street. He and his friends went there and found a safe that had been torn apart after being blown through a wall. Inside was a lot of melted silver coins. He and his friends were examining their find when a policeman found them and threatened to have them all shot as looters!

Mum either lived in Trowbridge in Wiltshire or was evacuated there, and became part of the Land Army.

Keith Hallett emailed me with these memories of the Blitz:

I sure remember going to bed in my "Siren Suit". We all slept in the cellar. Bristol Council offered to reinforce the cellar at 29 Midland Road. If Dad allowed them to place a SHELTER HERE sign outside the shop, he agreed and they came in and erected steel posts which held steel I beams, to hold up a corrugated steel ceiling in the cellar. The idea was that if the shop was hit this steel shelter would protect the occupants. If you go by the shop sometime you may still see under the right side shop window a steel plate with ventilation holes that was placed by the council to provide escape from the shelter.

My Dad and Uncle built two tier bunks all around the cellar for us to sleep, and a wide stairway was constructed for quick access just inside the shop door. When the air-raid siren sounded we might have about 25 to 30 people down in the cellar until the all-clear. My Aunt and Uncle's home was damaged at Filton, so they moved in with us. Then

other friends lost their home. Dad welcomed them in, so we had 3 families - 10 people living above the shop for quite some time during the Blitz.

In the cellar we felt pretty safe from incendiary bombs, but if the Jerry's started dropping their heavies, we ran to a big warehouse situated behind 29 Midland Road with the entrance around the corner on Waterloo Rd. This company built a bunker covered with sandbags about 20ft high, and considered pretty safe. This is where the Siren-Suit came in handy, we were already bundled up warm enough to run outside and around the corner to the bunker.

I remember really being afraid of the Blitz when we had to do this maneuver. The distinctive sound of the Jerry bombers overhead, the sound of bombs exploding in the area, our mobile guns firing back as the searchlights tried to pick out a Jerry, just a frightening experience for a little chap age 6 or running for his life, along with his parents. One of the things the Jerry's did that really scared us was dropping the parachute flares, they floated slowly down and lit everything up like daylight. We felt much more vulnerable when our homes were illuminated like this.

Bombs burst water and gas mains. When the water was on we filled the bath tub, and every available bucket. Leaking gas caused many a home to explode. Later on during the war I remember water pipes being laid in the gutter along Midland Road and elsewhere in Bristol, to make them easily accessible in the event of a bomb hit.

I'm sure you have heard about the heroism of Mr. George Jones, he was employed by the Bristol Gas Company and lived at Folly Lane, not far from my Grandparents who lived at 13 Alfred St. and Queen Victoria St. One of the first major raids on Bristol was in November 1940 and incendiary bombs landed on top of the large gas storage tanks at the corner of Days Road and Folly Lane - St. Philips. George climbed to the top, some 70ft high and kicked the incendiary bombs off. During the raid he again climbed up to seal off holes in the tank sustained by flying shrapnel. These acts of heroism earned George Jones the George Medal. This part of Bristol was home to so many families who owed their lives to this man. I am proud to say I knew him personally.

Mr Hallett also sent me these pictures of Bristol during the blitz :-

Bristol ablaze after a bomb raid

The King visits bomb torn Bristol

Wine Street

Bryan Bignell, who provided the photographs on the St. George pages, provided this account of the the Blitz.

The worst raid happened on the night of Sunday, 24th November 1940. Me and my parents were attending the evening service held as usual in the Evangel Mission, King Street, about half a mile up the road from our home. The service was interrupted by a Air raid warden coming in and shouting for everyone to get in the shelter nearby as the raid was getting more intense. I clearly remember the preacher who was a Mr. Everson, saying he was surprised by the lack of faith the congregation had as they all moved towards the door.

However my father had to report for duty at Air Balloon school where he was based as a warden, so he and my mother and me ran back home. Considering my mother was pregnant with my sister Janet (Philip Budd's wife) [Philip Budd provided information about Len "Uke" Thomas], it was quite a risk to take.

I will never forget as we ran down past the Kingsway cinema towards the brow of the hill by the Rodney pub from where you can see a good view of the city, how much it was like a huge firework display as literally hundreds of German flares were floating down illuminating the city. While we were on the way home a bomb landed on the junction of the Kingsway and the main road not far from the chapel which we had just left, but we were to far away by then for it to effect us.

Dad told us to keep in as close to the wall as possible and as soon as we arrived home saw a safely to our Anderson shelter at the bottom of the garden, while he went of with his tin hat on to put out the incendiary bombs etc. We were in the shelter all night on that occasion so there was no school on the Monday.

The Blitz was a period between September 1940 and May 1941 when the German air raids were a nightly event sometimes they lasted most of the night. There were also quite a few during the daytime and one in particular affected us as a family. One of the main targets for the bombers were airfields and Aircraft manufacturing plants of which Bristol had one of the largest at Filton, and my father worked there as foreman in the Toolroom. He also was one of the companies team of Air Raid wardens whose job it was to patrol the site during air raids, to put out incendiaries (fire bombs) before they could set buildings alight. The rest of his mates from the Toolroom went to two air raid shelters allotted to that department, half in each.

The Air raid in question was on Monday 25th September 1940 it was a big one by German standards, and they lost many planes shot down by our fighters or guns. The raid was totally directed at Filton and there was much damage; although he was outside, and not in the shelter my father was unhurt physically. When he returned home much later than usual, he broke down in tears and wept for quite a while.... one of the shelters in which half of the men in the Toolroom were situated, received a direct hit from a German bomb and everyone was killed. He was late home because he had been recovering the bodies of his friends from the debris.. .it was the only time I ever saw my father weep.

I was attending school at Summerhill on the day in question, because the raid was in the afternoon we had to go the school air raid shelter. Our teacher was one of the school wardens and was outside on patrol with his steel helmet on, which was lucky for him because he was hit on the head by a piece of Shrapnel (bits of exploded anti-aircraft shells). I and several of my mates did see some of the air fights between our fighters and the Germans, as the view of the sky over Filton was good from Summerhill.

My mother had gone down to town to do some shopping and was in Jones' department store when the raid started. She, like everyone else had to go to the shelter, and while she was there someone said she had heard that the works at Filton were being heavily bombed. Mum always said afterwards that it was probably one of the worst moments of her life, and she prayed.

I remember that we went down to Paignton in Devon for a few days break and the first night we were there they had an Air Raid, and everyone rushed to the Bomb Shelters except us (because we had grown so used to it). We didn't get much time on the beach because all the promenade was fortified with barbed wire, but they removed a special section for 1 hour in the morning and again in the afternoon so that people could go on the beach for a quick swim.

In the article above Bryan mentions the Anderson Shelter. These were devised by Sir John Anderson and by September 1940, 2,300,000 had been distributed. They were extremely tough and the basic corrugated steel construction was still in use for defensive works when I was in the army in the 1990's.

Bryan also wrote an article for the BBC WW2 People's War series.

Two civilians emerge unscathed from a battered Anderson shelter.

Image from the Home Sweet Home Front (Internet Archive) website

More about these shelters can be found at the these sites.

The corrugated steel construction being used 50 years later

Me in Denmark, around 1990

A family friend, Marge Hodgeson, remembers that the authorities built a heavily reinforced air raid shelter in her parents garden. The shelter was meant not only for her family but the neighbours as well. She remembers that when the house was demolished after the war it took a couple of men with sledgehammers just over a day to complete the

work but that they had to call in a crane with a demolition ball for the shelter, even then it took them three days to remove it.

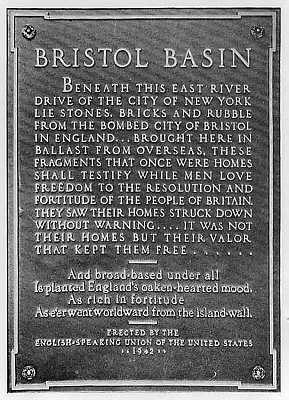

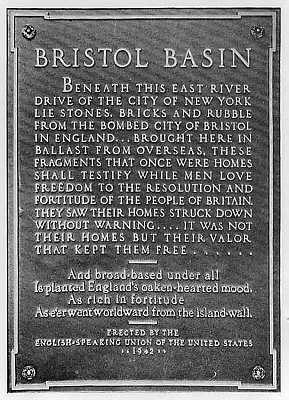

Mr Hallett also reminded me that much of the rubble from the bombings in Bristol ended up in New York. It was used as ballast in ships returning to America during the war.

Plaque in New York

The plaque reads :-

BRISTOL BASIN BENEATH THIS EAST RIVER DRIVE OF THE CITY OF NEW YORK LIE STONES, BRICKS AND RUBBLE FROM THE BOMBED CITY OF BRISTOL IN ENGLAND... BROUGHT HERE IN BALLAST FROM OVERSEAS, THESE FRAGMENTS THAT ONCE WERE HOMES SHALL TESTIFY WHILE MEN LOVE FREEDOM TO THE RESOLUTION AND FORTITUDE OF THE PEOPLE OF BRITAIN, THEY SAW THEIR HOMES STRUCK DOWN WITHOUT WARNING.... IT WAS NOT THEIR HOMES BUT THEIR VALOR THAT KEPT THEM FREE........

And broad-based under all

Is planted England's oaken-hearted mood,

As rich in fortitude

As e'er went worldward from the island-wall.

ERECTED BY THE

ENGLISH-SPEAKING UNION OF THE UNITED STATES

1942

I believe the Bristol born film actor Cary Grant was present at the dedication ceremony of this memorial.

POWs

On my Bristol Help pages, Irene Payne asked about the POW camp in Ashton Gate. In February 2008, I was delighted to get an email from

Kathleen Woodward who said...

I lived in Bower Road, Ashton from 1937 until 1956 and well remember the number of POW and Polish camps in the district. The Polish camp was near Ashton Drive - my friend and I used to walk by it on the way to Pit Ponds where we fished for tadpoles. The Germans were often seen in the neighbourhood walking around in their distinctive POW uniforms. Some of the neighbours befriended them which caused a lot of bad feeling, as they were encouraged to try and sell small wooden toys they had made in the camp. I remember one time two of them leaned on our front gate looking at my little sister playing and my mother rushed out and took her into the house. I recall towards the end of the war the German speakers in my class at school were taken to a hall in Bedminster to entertain German prisoners by singing German carols , and taking around

refreshments. I still remember being surprised while we were singing "O Tannenbaum" a group of them joined hands and started singing rather loudly what I later realised was the Red Flag.

Americans had been stationed in the Bond Houses in Winterstoke Road, Ashton Gate, and when they had gone back the buildings were used to house POWs.

There were other POW camps at Wapley, Yate and another at Winterbourne.

Street Parties

The end of hostilities was obviously a great relief for everyone and street parties were organized all over the city to celebrate Victory in Europe, VE Day. Thank you to Corrie Rutter and Bryan Bignell for supplying these photos.

Sources & Resources

Bath Blitz Memorial Project - 12 miles away, Bath also suffered

Bristol Archives: The Bristol Blitz: Sources for Research

Civvy Street in WWII (Internet Archive) - Tom Fletcher's account of living in Bristol during WWII

Daily Mail: The Blitz in Colour - Includes colourized film of the aftermath of a raid

Fishponds Local History Society: Blitz War Memorial - A register of those who lost their lives due to enemy action in Bristol and surrounding districts, 1940-1944

Luftwaffe Over Bristol 1940/44 - by John Penny

Night Blitz: November 1940 to June 1941 - The night raids on Bristol

Paul Plumley's evacuation from Bristol

This page created December 1, 2000; last modified January 25, 2022